The Purpose of Plastic: 'Toy Story'

Read this review and more at AnthonyReviews.com

One of the things I respect so much about the Toy Story franchise is its blend of a cynical viewpoint on the world with the spice of childish allegories. The plastic members of the cast, like children, see how tiny they are in comparison to the great world of scary things out there. They find solace in structure, distraction, and playtime. It is a worthy exercise to think about what kinds of lessons, especially large ones, children are being taught through these incredibly beloved films.

When thinking about these movies, imagine my surprise when I was hit with the realization that these films seem to have a lot to say about religion, with the child characters acting as gods in a world of mortal plastic. Christianity seems to be something that unintentionally seeped its way into the morality of the films themes. In four parts, I will be looking at each of the Toy Story movies and analyzing their theological themes and the conclusions they draw through their characters.

Seen through this lens, the original Toy Story becomes the story of two Christians in a church. One has known God for years and because of the close relationship they share thinks they know what's best for everyone. The second is a new part of the church, who doesn't understand the religion but is blessed with a lot of favor. The first Christian learns to humble himself and has his eyes opened to learning new things from those with less experience than him. Just because he was right doesn't mean he has the right to think of himself as better than others. The second Christian learns the truth of his existence as a toy, and comes to grips with how it is a blessing.

This allegory begins from the first scene of the film. Andy as a deity is supported by the cinematography, which specifically leaves Andy above the frame of every shot for the first two minutes of the film, keeping us at the toys’ eye level (which may be for the best, considering the ghoulish look of Andy's 1995 animation model). The playtime scene teaches us about the power dynamic of the room. Andy literally controls all of the toys and brands them with his name upon their soles as a reminder of the purpose of their souls. In Christianity, the name of God is similarly treated as something sacred.

As you might have guessed, Woody's faith in Andy is stronger than anyone else's in the film, but continues to be shaken when things change. While the other toys have fear about how Andy is going to take care of them if new toys are introduced, but Woody trusts Andy to take care of them. This becomes a reoccurring theme throughout these films, where everyone loses faith in Andy except Woody.

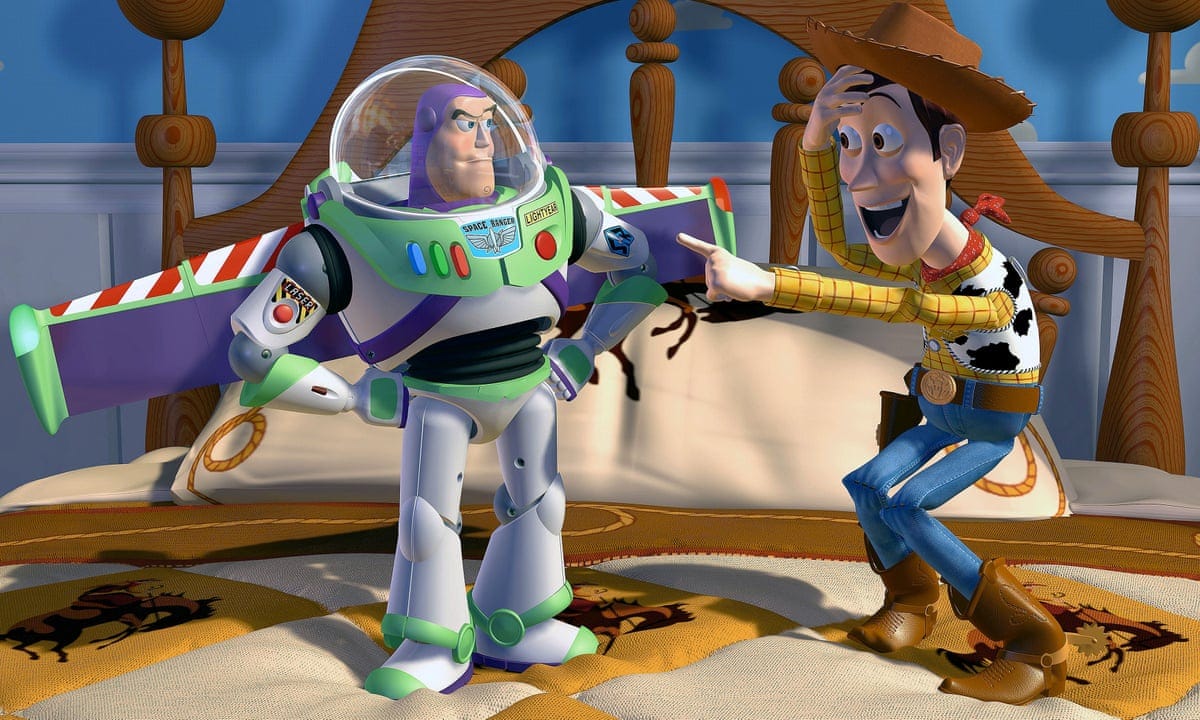

Buzz's arrival does this when he literally dethrones Woody as the top dog. Considering that Buzz doesn't believe in the same understanding of Andy that Woody has, this is an ironic twist. While Buzz thinks of Andy as the "chief" of this room, he doesn't recognize him as player nor himself as plaything. Like someone new to a faith, Buzz doesn't have a strong grasp of who this deity is, nor his relationship to them. This gives Woody a sense of prideful superiority in his knowledge compared to Buzz's naivety, even though Andy is pleased with Buzz even though he is disillusioned.

This is where the religious allegory becomes very clear to me. It seems that in his fit of jealousy, Woody has convinced himself it's alright to see himself as the rightful top of the toy society even if that's not what Andy wants, because Woody has a stronger understanding of Andy than Buzz does. But Buzz, even in his naive state, recognizes Andy's authority. Woody is the one who has disillusioned himself into thinking he is superior even though Andy has clearly set Buzz as the new head of the room.

That's when everything changes. Woody and Buzz are thrown into the real world, represented mostly by Sid's house, where they must fight to return to Andy. Sid has no respect for the toy/child relationship that Andy's toys hold dear, and his room's inhabitants suffer because of it. Woody's pride took over his actions, so that he was no longer thinking of Andy. And thus he was cast out and must overcome that pride in order to return. This is the transformation that takes place not only when he talks to Buzz (who we will return to in a moment) in the milk crates, but when he humbly goes to Sid's "cannibal" toys for help. His religious transformation is from a prideful gatekeeping Pharisee into a true servant to Andy.

Buzz has a similar transformation in Sid's house. His naivety is challenged, and his faith in himself over his acceptance of his place as plastic is punished when he loses his arm. Woody wasn't able to convince him that they are toys, but after Buzz accepts that on his own, it is Woody's transformation that is able to give him hope in Andy again. When Woody tells him how significant he is to Andy, it gives Buzz the strength to recover from the depression of realizing his place in the world, and to accept it. Before, Woody was telling him that he was a toy as a way of demeaning the space ranger and placing himself on a pedestal. But now that the cowboy's arc is complete; he is teaching Buzz that Andy really wants him, for Andy and Buzz's sake rather than his own. Thus, both their arcs are resolved together, and the finale can commence with both of them understanding and meshing each other's beliefs with their own.

As I will be stating throughout this series, I am not saying that this is what the creators clearly intended the reading of the film to be. Like many critics (though fewer as of late), I believe in the death of the author's intentions. However, modern Christians might be able to learn a thing or two from Toy Story. So often what I hear from people who have had bad experiences with the church is that it's just full of prideful, judgemental people who care more about their social status than actually putting into practice the Christian doctrine. Considering the main commission of the church is ministry, it's worth taking a page out of Woody's book and learning to check the nature within oneself.